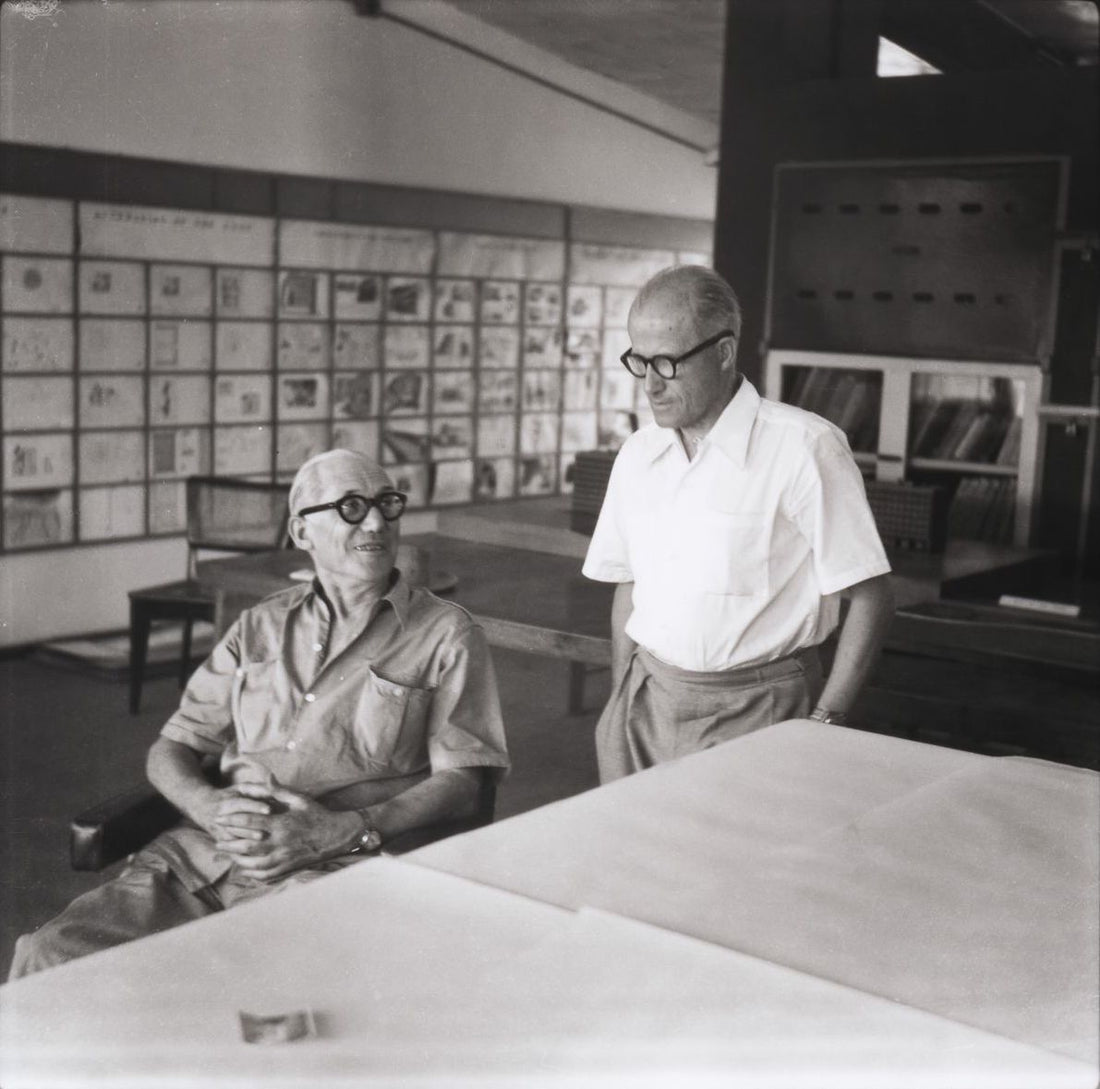

When Jawaharlal Nehru the first Prime Minister of post-Independence India invited famous French architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret to design the utopian city of Chandigarh, he inadvertently set in motion of series of events that changed mid-century modern décor forever. The architect better known as Le Corbusier (left) was a visionary but it was his team of experts headed by his cousin Pierre Jeanneret (right) who executed his grand plans.

The two had a brief falling out during World War II when they found themselves backing different sides but buried the hatchet in 1950 when Le Corbusier persuaded Pierre Jeanneret to make the voyage to Chandigarh. Once there, his love for the city was so deep that even though Le Corbusier left in the midst of the building process, Jeanerret stayed on to complete the task until the final years of his life.

A hallmark of his work is his brilliant understanding and acute sensitivity to the use of materials. He worked with them in a manner that didn’t make them yield to his will but rather brought out their innate beauty. Working with essentially geometric forms, Jeanneret’s teakwood furniture exudes the warmth and nature of the materials. The signature drafting compass shaped legs can be seen on a whole range of designs from chairs to benches to tables and desks.

As Chandigarh moved on from its roots and people started discarding old furniture in favour of more contemporary décor, many priceless Jeanneret pieces were found languishing in junkyards or dumped on the terraces of government buildings. Salvaged and refurbished by a few keen-eyed dealers in the 1990s, Pierre Jeanneret’s work has come out of the shadows of Le Corbusier’s fame. His work has had a resurgence amongst antique collectors and interior décor enthusiasts all over the world making Chandigarh take better care of its modernist heritage and rarer to find these masterpieces.

Jeanneret works have made the journey from the scrapyards of India to the ultra-luxurious homes and offices of design connoisseurs making these minimalistic yet functional pieces of furniture that were once positively bourgeois suddenly utterly chic.